How to be Creative

At Kenzai we spend most of our time working on what I think of as “the easy stuff.” This is things like eating the right food and doing the right kinds of exercise to get the physical results you want. In my mind, this is the easy part of wellness because if we add input "a” at the top of the equation, the laws of physics insist you'll get "b" at the end, every time. Of course sticking with this so-called easy stuff is actually pretty nuanced and difficult, which is why we make programs and structures to guide people through the process.

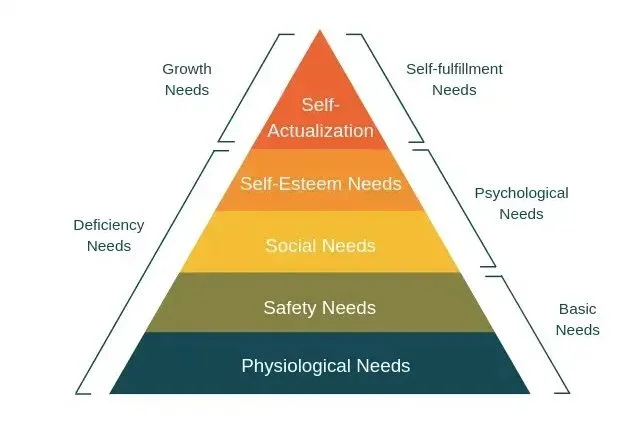

For me, the “hard part” of wellness is helping people nurture their human spark and find activities that help them, to borrow from Maslow’s Hierarchy, self-actualize to their full potential.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, a framework for thinking about what’s required to live a happy and rewarding life.

We always say at Kenzai that the goal of fitness isn’t to have great abs or thighs but to have a body that supports you in whatever endeavor you want to pursue. Yes, being fit will make you a better athlete and more confident at the beach, but it will also make you a better thinker, a sharper employee, a more engaged community member, and a more creative artist. It's this last point I want to look at in this article, because we often have newly healthy people wanting to do something with their unlocked creative energy, and not knowing how to start. It's not easy!

Today we'll cover the best way to get started making your own art, no matter what category it falls into.

But first we need to talk about book reports.

One year at my daughter’s school, she had a reading response essay assigned every week. The teacher provided a list of questions — things like, “Which character impacted you the most?”, and she had to write a page on the chosen question with supporting details. Pretty standard stuff, but it was the first year she had been asked to write so freely without guardrails, and she was having a lot of trouble. There were a lot of frustrated afternoons saying, “But I don’t know what to write!”

At first I didn’t try to help her too much. This was part of the process, I figured, struggling to find a theme, then working your way to elaborate on it with details and examples. It’s what every writer goes through. You’ve got to push through those tough moments and find the flow of your writing. You can’t quit when you feel like you don’t have any ideas. But even after a few weeks she wasn’t finding success and was getting really stressed, with lots of procrastination and tears. So I started sitting down with her every week and working through the task together.

“So, which character had the most impact on you? Which one made you feel the most emotion?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well, which character did you like?”

“This one.”

“Ok, and why?”

“Because she fought against the bad guys.”

“So, you could say her courage and bravery were inspiring to you.”

“Ok, how do you spell inspire?”

“Wait, but that’s just my idea, you’re supposed to come up with your own idea.”

“But I don’t have any ideas!”

This is how it would go, until I would wave the white flag and let her write what I had spoon-fed her, just to get through the homework and on with the day. We did this every week all through the fall and winter. Some weeks she’d have a few of her own suggestions, but usually I was doing the heavy lifting helping her find themes and interesting angles to write about.

We had a parent-teacher conference at the end of Fall break, and her teacher gave lots of compliments about how well my daughter’s weekly reading response essays were going! I didn’t say anything, just smiled and nodded (while gulping nervously). She was only doing so well because I was helping ghostwrite her essays! Was I robbing my kid of the chance to learn how to write well by being too involved?

But over the past few months, something interesting has started to happen. We’ll sit down to work on the reading response essay, and my daughter will begin by asking herself the same kind of questions I used to prompt her with:

“Hmm… what do I think the lesson of the story was? I can think of a few things, but this one has the most interesting examples to write about.”

She then proceeds to knock out the assignment quickly, in her own way, but following the method we informally figured out through all those painful weeks of me helping her. I give all due credit to her teacher and school, but I can hear my own writing approach coming out of her mouth, with her own twist on it.

Watching this process has been reassuring for me, because it backs up a philosophy on education and artistry that has served me well in my creative endeavors.

When you set out to create something artistic, there’s a pressure to search your soul and pull out some unique piece of art that the world has never seen before. So you sit down, do your best, and are usually disappointed by the results. Your first attempts at something are dreadful. It’s nothing like the soaring creation you envisioned. In fact, not only is it ugly, it’s unoriginal! You say to yourself, “Ugh, this looks/sounds/reads just like this other artist, but way worse! I’m a hack!” When you set out with the goal of making something totally original, you inevitably end up feeling like a failure or a fraud.

But if you think about it, in no other field is anyone expected to produce unique work right from the start.

For example, I’m an aikido student. If I went to class and told my sensei that I had figured out a better way to do a throw, and would only be doing my version from now on, he would laugh me out of the dojo. I’m not there to create my own techniques, I’m there to learn the system as closely and accurately as possible. During class, if my wrist is rotated just 15° off where it should be, I’m corrected on it and made to repeat the technique until its right. It’s only when a person attains a 3rd or 4th degree black belt that they can start even thinking about new techniques and variations.

Throughout human history, there’s been an understanding that producing original, creative output is the last stop on your journey as a maker, not the first. The blacksmith spends years as an apprentice, more years as a smithy, until finally being able to craft unique works as a master ironworker. The famous chefs you see on TV didn’t waltz into their positions full of groundbreaking cuisine ideas; they started as line-cooks then sous chefs and copied 10,000 dishes before ever serving one of their own.

The entire concept of martial arts, or apprenticeship in a trade, is built on the idea that as a beginner you don’t know enough to produce anything new or unique. So just watch, learn, and practice.

Why then, do we beat ourselves up about imitative and derivative work when we try to make our own art?

Why do we deny ourselves the benefit of an apprenticeship?

In the case of my daughter, why was I expecting a nine-year-old to start writing structured, well composed, evidence-supported essays from the first day of school? What she needed was an apprenticeship, not because she’s not smart, but because she needed to see how to do it a few dozen times before getting the knack for it herself. This is just how humans get good at stuff.

As you start on a creative endeavor in your own life, don’t be shy or embarrassed to spend months or even years simply imitating what others have done. That time is your apprenticeship. There’s no better way to learn how to do something. Also, don’t worry that because of your apprenticeship you’re never going to be your own artist. Your personality will start coming through in ways you might not even realize, and over time your technique will crystalize into something beautiful no one else can do.

When I train with the other students in the aikido dojo, I notice that even though everyone is trying hard to copy the exact techniques, they can’t help to inject some of themselves into them. One person uses more finesse and circular motion, another uses power and straighter lines. It doesn’t matter how hard a person is trying to do an exact duplicate of the original, their personality will seep through, and with enough time and practice, the art will become their own.

A good example of this is Picasso. He had to first learn classical style before knowing how to subvert it into new, startling forms. Compare these two paintings, done 20 years apart:

Portrait d'Olga dans un fauteuil - 1917-1918

Portrait de Dora Maar, 1937

People will see the second painting and think, “Why, that’s not so difficult! Even I could paint something like that.” But without a foundation in the classical style, Picasso wouldn’t have found his way through to his groundbreaking later work. And if you try to leap frog straight to brand new, unique art, your results will frustrate you to no end.

If your goal is to put something out into the world that’s fresh and unique, follow this plan and you’ll find success comes more smoothly.

Kenzai’s 7-Stages of Creating Your Original, Unique Art

Find an artist you like. Think of this as the master who you’ll be apprenticing under. It can be a painter, a musician, a software developer, a chef, an athlete, or even someone in business who has a strategy you admire.

Begin your apprenticeship, even if it’s just watching YouTube videos alone in your room. Your first goal is to copy the master as closely as you can, imitating their work step by step. Of course if you can actually work in person with the master, this process will be a magnitude more powerful. There’s a nice Japanese phrase here, “waza o nusumu,” which means “stealing the technique.” A master won’t just tell you all their secrets, you have to observe closely and steal whatever you can glean from their method.

Completely forget about originality for now — just copy, copy, copy. This could take weeks, months, or years. Enjoy the process of gaining a skill until you can produce a reasonably close approximation to what the master makes. It doesn’t have to be perfect, we’re copying here, not forging.

Through all of this copying, you’ll start to see “cracks” in the technique. These are little places where you think to yourself, “Hmm… she does it like that, but if instead I did this it would create something a little different.” Once you can consistently make a good copy, it’s time to turn your attention to these cracks, and pry them open.

Keep making copies, but widen those cracks more and more. Sometimes a crack opens to a rich vein of creative ore that leads to whole new techniques you never could have imagined. Chase down those veins, this is where the art becomes yours.

With time and diligence, you’ll begin to see that you’re no longer copying or imitating someone else — you’re doing your own original art, with roots in the work of those you admire. The cracks have grown so large that they now make up the main body of the work.

Congratulations, you’ve taken the same journey that all artists have taken, and can keep working on your technique for years to come. Perhaps one day some aspiring artist will start copying you!

Don’t tell yourself you’re not a creative person because your first attempts feel uninspired. Nurture the artistic, innovative side of yourself with strategic apprenticeships, and grow into the artist you’re meant to be. Having a rich, creative life is the capstone of sustainable wellness! Share this apprentice approach with the friends, family, and 4th graders with book reports in your own life.