Understanding Non-linear Progress

Imagine you run a business that has both company vans and company cars. It’s been a good year and you have some money in your budget that allows you to make a bulk order for either new vans or new cars. You can choose to replace only one of the fleets — either all new vans, or all new cars.

The vans get 10 miles per gallon, and can be replaced with a newer model that gets 20 miles per gallon.

The cars get 20 miles per gallon, and can be replaced with a newer model that gets a whopping 50 miles per gallon.

All vehicles travel 10,000 miles a year.

The question is, which type of vehicle do you replace to save the most fuel (and money) for your company?

What do you think?

Nearly all people feel an instinctual pull towards choosing the 50 mpg cars. The move from 20 to 50 mpg seems like a big boost. It’s more than double, and feels bigger than the move from 10 to 20 mpg. It just seems like the right answer.

However, the correct answer is to replace the 10 mpg vans, and it’s not even a close call. Let’s break down why.

The vans currently drive 10,000 miles a year at 10 mpg, meaning that they use 1000 gallons of gas in a year.

The new model van would drive 10,000 miles at 20 mpg, resulting in a yearly use of 500 gallons a year.

Upgrading the vans saves 500 gallons of gas per year. (1000 - 500 = 500)

Compare this outcome with the more fuel-efficient cars.

The old 20 mpg cars, at 10,000 miles a year, use 500 gallons of gas annually.

The new 50 mpg models at 10,000 miles a year, will use 200 gallons of gas a year.

Upgrading the cars would only save 300 gallons of gas a year. (500 - 200 = 300)

Choosing to upgrade the vans results in 66% greater fuel savings. That’s quite a difference, and quite a thing for your intuition to get so wrong!

Why does your brain make this error?

The mistake comes because humans are accustomed to thinking in linear functions. If you have $2 you can afford one coffee, if you have $4 you can afford two, with $6 you can afford three, and so on.

A linear progression for the amount of coffees you can obtain at $2, $6, and $10 increments. More cash, more coffee.

Most things we deal with are linear, and so our brain knows it can rely on linear thinking to solve things.

But miles per gallon isn’t a simple linear equation, it’s a ratio. The gas used is the inverse of that ratio, which doesn’t follow a straight line. This is called a curvilinear progression.

The math here is tricky, but essentially, because “gallons” are represented in the equation twice, you get a curve that will gradually smooth out into a nearly straight line.

The first part of the gallons-to-mpg curve is very steep, then begins to flatten out, and will keep flattening all the way into infinity. This means that fuel efficiency gains made at the start of the curve will always outweigh later gains.

You can see this much more clearly when we divide the line into sections like this.

As counterintuitive as it may seem, nothing is ever going to beat going from 10 to 20 mpg vehicles. Even if you found incredible future-tech cars that got 1000 miles per gallon, you’d still only save 490 gallons of gas compared to 500 from the better vans.

What does this have to do with fitness and your health? Everything!

Your fitness is also a non-linear function. As an organic lifeform, your body is nothing but a big batch of ratios and trade-offs. When you want to get in better shape, your graphs will be curves upon curves.

For example, let’s say you want to get stronger, so you start lifting weights. In week 1 at the gym you can do a barbell curl of 20 kg (an empty bar). You decide to add 5kg a week as you get stronger. In week 2 you can curl 25 kg, in week 3, 30 kg, and so on. In a linear world, in 52 weeks you’d be curling 280 kg (617 pounds). Given that the world record barbell curl is 114 kg, clearly linear function doesn't describe what will actually happen here.

Becoming stronger, just like fuel efficiency, goes quickly at first, but soon starts to see the curve flatten out into diminishing returns. Your muscle power isn’t the lone variable in the equation, your body has to keep muscle in a ratio with bloodflow, tissue maintenance, hormone balance, and energy usage. At a certain point the body can’t add any more easy muscle and you start to hit your natural plateau.

As an aside, this is why anabolic steroids work — through tampering with the body’s natural ratios, a bodybuilder can delay the flattening of the muscular plateau (with many unhealthy side-effects for all the other parts of the body that depend on those ratios not being tampered with).

Endurance sports have the same limits. A new runner might say to himself, “This week, I’ll run 1km, next week I’ll run 2, and by the end of the year I’ll be able to run 50 km ultra-marathons!” This runner would be ok up to about the 10km mark. Then he would find each kilometer further becomes harder and harder fought. While it is possible to go from 0 to 50km in a year of running, it’s a far more complicated process than just adding a kilometer a week. It requires specialized training, nutrition, and dozens of hours per week of to coax out ultra-long distances from a body that resists such extremes of exertion.

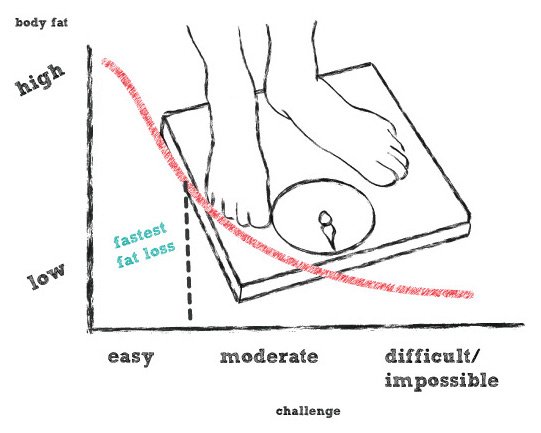

We see the same curve with weight loss. The body can somewhat easily shed the first few kilograms of body fat. But as your body fat approaches what your body considers its essential lower limit, ratios start kicking in and you have to fight hard for each percentage of body fat lost. It’s just as hard to go from 10% to 9% body fat as it is to go from 30% to 20% body fat.

Now that you’ve got the concept of how your body uses curvilinear functions, there are two big shifts you can make in your approach to fitness.

1. Don’t get attached to the easy gains that come at the start of a fitness effort.

Getting started on a new exercise or eating regimen is a lot of fun. Not only is everything still fresh and novel, you’re getting results. You feel stronger, your posture improves, you sleep better, fat-stores thin out and your numbers start moving in the right direction.

What most people don’t realize is that they’re enjoying the steep part of the curve. The first few weeks are when you usually get the biggest fitness improvements for the least amount of effort.

The problem comes as the curve begins to flatten out. This tends to happen at the worst possible time, right when the shine of your fitness effort is wearing off. Suddenly, not only are you “over” all the tedious eating and exercise chores, you’re not getting the boost of seeing the same big results. This is a tough combo, and someone who was completely into-it and motivated just a few weeks earlier can see their drive drop to nothing in a scarily quick amount of time.

You can inoculate yourself against this by internalizing the fact that progress is non-linear. When you’re on the steep part of the curve, enjoy it, but remember that it won’t always be this way. Don’t hook your motivation to the falling star of big early results. The period when big results stop coming quickly doesn’t mean the end of results altogether.

This is why we always recommend a person take on a fitness effort for a set amount of time, and see it through to the end. If you know you’ve got “X” number of days of training, how fast or slow your results come becomes less important. You’ve committed to a period of diet and exercise, and will get the effects of that period. Sometimes it’s front loaded, sometimes it’s a smooth line, and sometimes we even see “late-bloomers” who hit a steep part of the curve near the end of training. Smart trainees don’t let the steepness or shallowness of the curve become a motivational roller coaster.

2. Shore up easy wins before spending lots of energy on the shallow part of the curve.

Once you see how much improvement happens at the start of a curvilinear function, it won’t take long for you to realize you get a lot of bang for your buck by working on parts of your life that are still in the 10 mpg range.

Let’s ask, “what makes a person feel fit and happy?”

Everyone has their own answer for this, but research shows the main factors are as follows:

Healthy, balanced diet

Good cardiovascular health

Healthy low body fat

Sustainable muscle mass

Consistent high quality sleep

Strong social support network (family and friends)

Good work/life balance

No major dependencies (alcohol, drugs, other addictions)

A meaningful, purpose-driven life.

That seems like a lot to work on, doesn’t it? It’s kind of intimidating when you think about how many things you have to do to get it right.

But remember, each of those factors will have its own non-linear progress line, and the biggest gains are at the top of those lines.

For example, to get the major benefits of cardiovascular health, you don’t need to be running long distances or putting in huge, sweaty cardio sessions on a bike or machine. Studies show the bulk of cardio benefits come with as little as 30 minutes of activity a day. Someone who decides to take a brisk walk around their neighborhood will get a bigger cardio boost than an experienced runner moving from the half-marathon to the full-marathon distance. Those sweet easy gains are there for the taking, and you don’t have to keep pushing into diminishing returns.

Look at that list of healthy-life hallmarks again, and ask yourself, “What’s the simple, top-of-the-curve action I could take for each of these factors?

Healthy balanced diet? I could stop eating fast food and pack my own lunch.

Consistent high quality sleep? I could move my phone to the other room so I don’t look at it at night.

Good work/life balance? I can stop checking email on the weekend.

Suddenly an intimidating list is becoming a series of bite-size, actionable things that don’t seem very hard at all. And the beauty is that with each of these easy wins you’re getting those big 10 - 20 mpg improvements to your life.

There are a lot of easy wins out there, just waiting for you to get started.

People like to feel like they're good at things, and you’ll often see someone tunnel into one very narrow aspect of life at the expense of others. A wiser approach is to reap your easy gains from as many categories as you can first, then dive into what interests you most.

Work smarter, not harder - more than a catchphrase.

If you spend any time in health and fitness you’ll soon stumble across the phrase “work smarter, not harder.” In most cases this is just advertising for a crappy supplement, a pseudo-scientific exercise technique, or an ineffective gadget.

Leveraging the power of easy gains at the top of curvilinear functions is the purest, most literal sense of working smarter, not harder. You’re getting more done with less effort, in a shorter amount of time. The math doesn’t lie.

The key to getting this right is to always be balancing the two competing methods of improvement:

Recognize when you’ve entered a stage of such diminishing returns with one wellness item that your efforts might be better spent working on the tops of other curves.

However, if you want to make advanced progress, stick with your efforts even when the curve flattens, knowing that there’s a lot more to be done after the easy gains have been locked in.

Finding the balance between these two boundaries is the sweet spot of wellness. You might not hit it all the time, but at least now you know where to aim!